Timeline: Three Sightings at the Hanford Nuclear Production Facility

"I threw a brick at it. That put a hole in it and it went down"

This timeline is to help you understand the key events and UFO sightings that happened at the Hanford Nuclear Production Facility during the Second World War (also referred to as the Hanford Project, Hanford Works, Hanford Engineer Works, Hanford Nuclear Reservation, and Hanford Site). It provides specific dates and times wherever possible. All claims are cited in the endnotes.

Key Events During the Second World War

December 7, 1941: The Japanese Military launches a surprise attack on the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The United States declares war against Japan (December 8, 1941) as well as Germany and Italy (December 11, 1941). This begins U.S. involvement in the Second World War.1

January 19, 1942: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt formally authorizes the United States Manhattan Project which is an effort to produce a nuclear weapon for use during the Second World War.2 While initial discussion about the project began on August 2, 1939, they had remained largely theoretical and designed to compete with a perceived effort by Nazi Germany to produce a similar weapon.3 The entry of the United States into the Second World War now accelerates this effort and prepares the project for an offensive intent.

December 21, 1942: Du Pont de Nemours and Company receives a contract to construct and manage the world’s first plutonium production facility. A site is selected in Hanford, Washington with construction beginning in 1943. This site is being constructed to advance the United States Manhattan Project.4

This event is significant as there are no known UFO interactions in Washington State prior to the introduction of this nuclear facility. It remains the contention of key figures in the UFO Research Community that there is a relationship between the development of nuclear technology and the presence of UFOs.5

October 10, 1943: Construction begins on the world’s first full scale plutonium production reactor at the Hanford Site. The reactor will be called “B Reactor” and represents a substantial advance in the United State’s ability to make fuel for an atomic bomb.6

September 6, 1944: “B Reactor” at the Hanford Site is completed and begins operation. This is the world’s first full scale plutonium production reactor. There will be an additional two reactors constructed (D Reactor and F Reactor) by the time the site is fully completed in April 1945.7

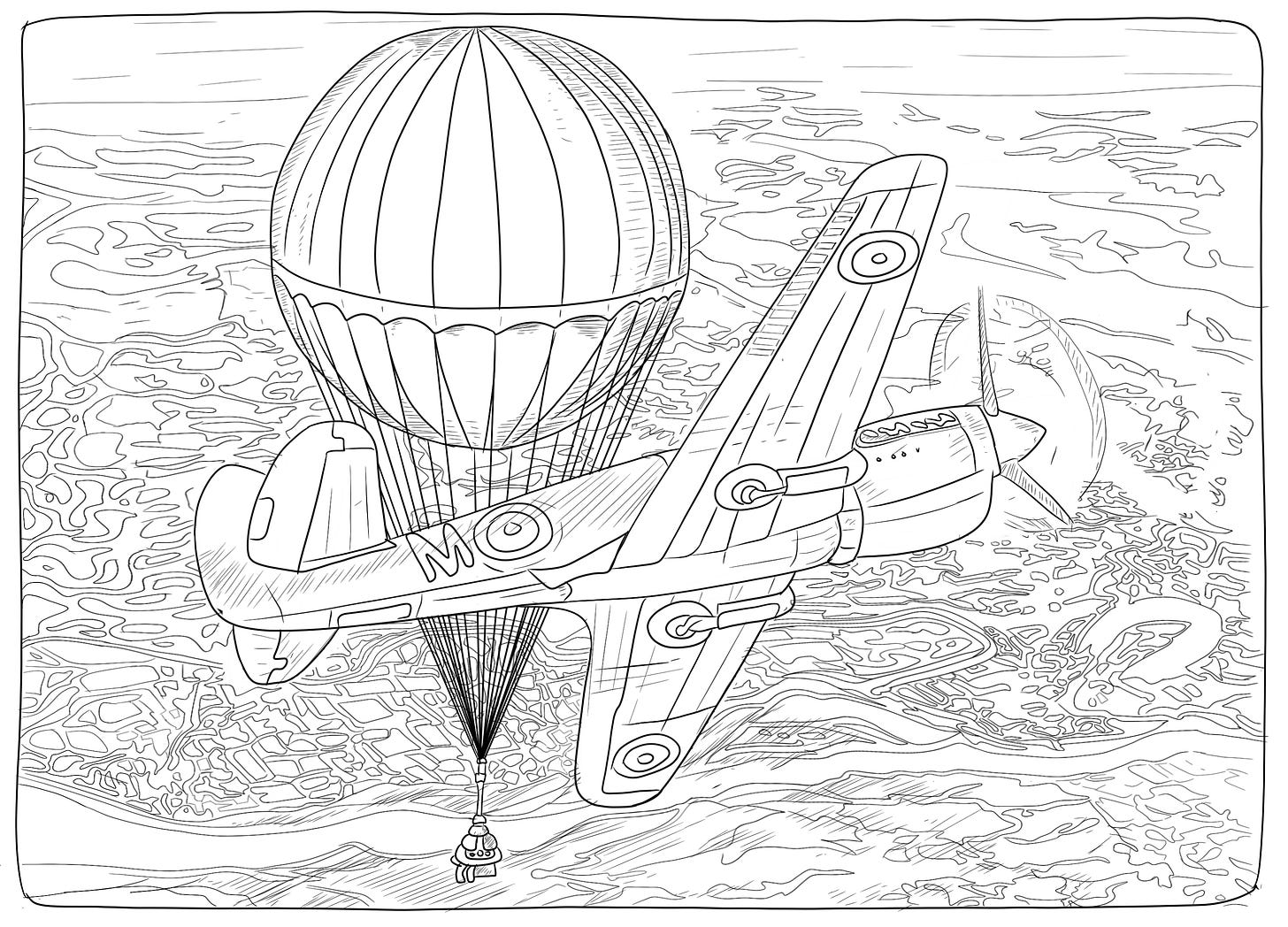

November 3, 1944: The Japanese Military launches the first “Fu-Go” Balloon Bomb into the Pacific jet stream. Each balloon carries four incendiaries and one thirty-pound high-explosive bomb. The intention of the program is to cause fires, damage, and spread panic across the continental United States. Approx. 9,300 balloons will be launched at the United States from Japan until the program is cancelled in April 1945.89

November 5, 1944: A U.S. Navy patrol off the coast of California spots the remnants of a Japanese Balloon Bomb in the ocean. This is the first time the United States discovers and identifies this new Japanese weapon. Between November 1944 and April 1945 there would be approx. 300 discoveries and incidents across the United States. Because the balloons are travelling immense distances with no guidance other than the wind, they are notoriously inaccurate and ineffective. The U.S. Military’s awareness of these balloons will influence their early interpretation of any unknown objects in the air.10 It remains the contention of some academics that any claims to have encountered a UFO during this period were actually the result of the Japanese Balloon Bomb program.

December 17, 1944: “D Reactor” at the Hanford Site is completed and begins operation as the world’s second full scale plutonium production reactor.11

c. December 23, 1944: Unidentified aircraft are observed flying over the Hanford Site on at least two nights beginning around December 23, 1944. It is unclear if these initial observations are made visually or using radar, however, a later report by the United States Fourth Air Force will indicate that unsuccessful fighter intercepts were attempted on at least one of these two sightings.12

These fighter intercepts are conducted from Pasco Naval Air Station which is located about 26 miles (42 km) southeast of the Hanford Site.13 A newspaper article after the war will indicate that “radar was installed at the [Hanford Site] hurriedly when we saw or thought we saw unidentified aircraft operating [in the area].”14 This is presumably a reference to these first sightings in December 1944.

A later statement by a fighter pilot sent on a subsequent intercept in January (Cdr R.W. Hendershot) will describe a single F6F “Hellcat” fighter being sent to intercept these initial radar contacts. At the time of his statement, he can no longer remember the name of the pilot flying the intercepts, but he indicates that radar clocked the objects moving “about as fast as a J-3 ‘Piper Cub’ aircraft” travelling northwest to southeast across the Pasco Naval Air Station. On both occasions, this unnamed fighter pilot was unable to make visual contact.15 For reference, the top speed of a J-3 Piper Cub is 85 mph (137km/h), the top speed of a Fu Go Balloon Bomb is 185mph (298km/h), and the top speed of an F6F Hellcat is 391 mph (629km/h).161718

January 4, 1945: United States Western Defense Command orders that no publicity be released concerning the Japanese Balloon Bombs to prevent public panic.1920

January 15, 1945: A battery of searchlights is moved from Seattle to the Hanford Site. The Thirteenth Naval District instructs fighters at Pasco Naval Air Station to use radar and fighter aircraft to identify anything that flies over the facility. The airspace is declared a “Danger Area” and a “Restricted Area” to prevent all accidental military and civilian flights. Naval Aviators are instructed to intercept and shoot at any unidentified aircraft they find.21

Undated Contextual Note: Further complicating the issue of what exactly is flying over the Hanford Site, U.S. Army Counter-Intelligence Agent, Vincent Whitehead begins flying the perimeter of the facility in an unspecified “artillery spotter plane” sometime after his arrival in Spring/Summer 1944.22 For reference, the J-3 Piper Cub was widely used for artillery spotting during the Second World War and it is possible Whitehead’s flights could account for some of the early radar contacts reported during this period.

According to Whitehead, he and another pilot check the fence perimeter of the Hanford Site via these flights “every morning.” On one occasion, he notes that they discover a Japanese Balloon Bomb flying directly overhead which Whitehead claims to have brought down personally from his aircraft by throwing a brick at it. He indicates the balloon crashes 1.5 miles outside of the fence line and is recovered by himself and his co-pilot on landing. The date for this incident is not specified and it is not recorded in any subsequent reporting by G-2 U.S. Army Intelligence.23

Assuming this story is accurate, this suggests that (1) there may have been issues sharing flight and radar information between Pasco Naval Air Station and the Hanford Site, (2) there were definitely issues sharing information on Japanese Balloon Bomb incidents between different military commands, and (3) at least some security incidents around the Hanford Site were withheld from broader military reporting so as not to disclose the top secret purpose of the facility.

Between January 15–23, 1945: Radar at Pasco Naval Air Station briefly picks up an aircraft over the Hanford Site. A single T6 “Texan” training aircraft is sent to intercept but is unable to make contact with anything in the area.24 This training aircraft is likely the plane piloted by Cdr R.W. Hendershot who, in his account, indicates that his intercept took place in an “SNJ” aircraft during the afternoon in response to two radar blips that were “very high” up in the air. The “SNJ” is another name for the T6 Texan.

As with other previous intercepts, Hendershot was unable to make any visual contact with the object he was sent to find but he would later state, that despite his lack of contact, it was his belief that “there was something there.”25 R.W. Hendershot’s account and subsequent written statement is not dated, though its presentation to noted UFO research advocate, Donald Keyhoe, likely places it sometime in the 1950’s not long after these events would have occurred.

Between January 23 – February 15, 1945: On January 9, 1945 a squadron of F6F “Hellcat” fighters from Air Group 50 arrives at Pasco Naval Air Station for ground support training. Lt. Cdr Richard Brown, Lt. (j.g.) Clarence Clem, and Ensign C.T. Neal are three of the Naval Aviators that are part of this training exercise.

On a date that is likely sometime after the intercept conducted by Cdr R.W. Hendershot, the three men receive a call in the Officer’s Club with a request to investigate another unidentified aircraft over the Hanford Site. Brown takes to the air in an F6F Hellcat, Clem positions himself in the Air Traffic Tower to coordinate radio communications, and Neal enters a second F6F Hellcat that waits on the tarmac on standby. During his intercept, Brown encounters an object that he describes as “looking like a ball of fire” hovering directly over the Hanford Site. He chases the object which promptly outruns him and disappears from radar travelling in a northwest direction. On returning to Pasco Naval Air Station, he describes the object as “so bright he had trouble looking at it.” There is no follow-up action taken after this intercept.

There are two additional intercepts that occur prior to the squadron leaving Pasco Naval Air Station on February 15, 1945. The second intercept involves a radar contact that disappears before Neal is able to get airborne to chase it. A third intercept occurs but the details are no longer memorable to the Naval Aviator (Clarence Clem) providing the account sixty-four years later in 2009. None of these three intercepts are acknowledged or written about in the squadron history that follows the war and there is no other documentation that corroborates this account.2627

January 25, 1945: Western Defense Command and Army Commands located at the Hanford Site request that an additional night fighter be based at Pasco Naval Air Station to respond to the recurring appearances over the site.28 It is unclear whether this permanent duty was ever assigned.

February 2, 1945: The first successful processing of plutonium at the Hanford Site is complete. A delivery is made to a representative of the Manhattan Project on February 3, 1945.29

February 12, 1945: The first traces of a Japanese Balloon Bomb appear in Washington State as two unexploded bombs are found 7 miles (11km) north of Spokane, Washington. There will be a further nine discoveries in Washington through the month of February (15th, 20th, 21st, 21st, 21st, 22nd, 27th, 28th, 28th). Most of these discoveries involve finding parts of a balloon on the ground. In one case on the 21st, a balloon remains airborne after it was reported and in another separate case (also on the 21st) a balloon is shot down over Suma, Washington by the Royal Canadian Airforce. Only one discovery occurs in proximity to the Hanford Site (February 15 – Prosser, Washington) where an intact paper balloon is found on the ground.30 Prosser is located about 27 miles (44 km) southwest of the Hanford Site.31

February 25, 1945: “F Reactor” at the Hanford Site is completed and begins operation as the world’s third full scale plutonium production reactor. The completion of this third and final reactor makes this the largest plutonium production facility in the world. There are only two other plutonium production facilities in existence, and they are small prototypes located at the University of Chicago and the Clinton Engineering Works in Tennessee. Their potential does not come close to the Hanford Site, which now has a maximum available output of 21 kilograms of plutonium per month.32

March 3, 1945: Paper fragments of a Japanese Balloon Bomb are found again in Washington State. There will be a further seven discoveries of intact balloons or balloon fragments through the month of March (10th, 10th, 10th, 10th, 13th, 13th, 13th). Only one discovery occurs in proximity to the Hanford Site (March 10 – Toppenish, Washington) where portions of a balloon were found on the ground.33 Toppenish is located about 41 miles (66km) southwest of the Hanford Site.34

March 10, 1945: A Japanese Balloon Bombs strikes a power line between Bonneville and Grand Coulee near Sunnyside, Washington. This knocks out power in the area triggering a backup power system for the Hanford Site. It takes about three days to return to full power which slows plutonium production during this period.

This account is offered by Col. Franklin Matthias, the U.S. Army Officer in charge of the Hanford Site, in an interview conducted in 1965. Notably, there are no traces of this incident present in G-2 U.S. Army Intelligence reports on Japanese Balloon Bombs around the time it is said to have occurred. Assuming this story is accurate, it further suggests that (1) there were issues sharing information on Japanese Balloon Bomb incidents between different military commands, and (2) at least some security incidents around the Hanford Site were withheld from broader military reporting so as not to disclose the top secret purpose of the facility.3536

April 1, 1945: More equipment from a Japanese Balloon Bomb is found in Washington State. There will be a further four discoveries of intact balloons or balloon fragments through the month of April (1st, 3rd, 19th, 30th). Two discoveries occur in proximity to the Hanford Site (April 19 – Wapato, Washington and April 30 – Moxee, Washington) where portions of a balloon were found on the ground in each case.37 Wapato is located about 44 miles (71km) west of the Hanford Site and Moxee is located about 42 miles (68km) west of the Hanford Site.38

Early April, 1945: The Japanese Military launches the last “Fu-Go” Balloon Bomb at the United States. At the time, there are doubts about the efficacy of the program and production is now limited by the recent destruction of a key hydrogen plant.39 Using a conservative estimate of how long a Fu-Go Balloon Bomb could stay airborne (about 50-90 hours),40 this eliminates the balloons as a potential explanation for unidentified flying objects over the Hanford Site by mid-April, 1945.

April 13, 1945: The Hanford Site completes an additional structure for plutonium production (the B-Plant) and finishes all site construction by the end of April. This now allows the facility to ship plutonium by rail to Los Alamos, New Mexico every five days. In May, the speed of delivery will be increased by moving from rail to guarded truck convoys. In late July, this will be deemed insufficient and the facility will begin direct shipments by air.

To accommodate these increased shipments, the facility (1) runs their reactors above their rated power levels, and (2) reduces the cooling period for irradiated fuel to potentially unsafe levels. Despite these dangerous developments in the spring and summer of 1945, leadership of the Manhattan Project will continue to demand increased production until the Japanese surrender on August 15, 1945.41

May 5, 1945: In Bly, Oregon, a Sunday School picnic approaches the debris of a grounded Japanese Balloon Bomb. At the request of the U.S. military, there has been no public acknowledgement of the program to prevent public panic. As they are unaware of what they are looking at, most of the picnic gets close to the debris when the bomb explodes killing the Reverend’s wife and five children attending Sunday School between the ages of 11 and 14. The Revered is the only survivor of the explosion. After this incident, the military breaks its silence and issues public warnings about the balloon bombs and gives instructions not to tamper with them. This is the first time the public becomes aware of the existence of the Japanese Balloon Bomb program.42

May 25, 1945: The last remnants of a Japanese Balloon Bomb are found in Washington State. This final discovery is made in Asotin, Washington which is not in close proximity to the Hanford Site. In total there have been twenty-five balloon bomb discoveries in Washington recorded by G-2 U.S. Army Intelligence. The vast majority of these have been recovered fragments of balloon bombs found on the ground. A further majority (21 out of 25) are not located within close proximity (defined by this author as 50 miles) to the Hanford Site.43

July 16, 1945 - 5:30am: The atomic age begins with the first successful detonation of an atomic bomb at the Alamogordo Bombing Range near Los Alamos, New Mexico.44

c. July 22, 1945 – 12:00pm: In early July 1945, Lt. Cdr Rolan D. Powell is transferred along with 12 other Naval Aviators to Pasco Naval Air Station. The U.S. Navy has selected them to form a new squadron and train for carrier operations in the Pacific.

On a date around July 22, 1945 Powell and his fellow aviators are at the Air Station when a “General Quarters” alarm sounds and they are directed to intercept an unidentified fast-moving aircraft that is now in a holding pattern above the Hanford Site. Six F6F “Hellcats” take to the air and arrive above the site at approx. noon on a clear day. Powell describes seeing a large, oval-shaped, streamlined object that is “pinkish” in color. The object is holding in place at about 65,000 ft and, according to Powell, emitting vapor around its outside edges from what appeared to be portholes and vents. In a later interview, he would speculate that the vapor was being discharged to form a cloud for disguise. In addition to these features, Powell estimated the size of the object as about “three aircraft carriers side by side.” Using the dimensions of a WWII-era aircraft carrier, this would make the object roughly 800 by 270 ft (244 by 82 metres).

All six pilots attempt to climb to co-altitude with the object, but they are limited by the technology of the time. The F6F Hellcat is rated for a maximum altitude of 37,000 ft. According to Powell, the pilots are able to push it to 42,000 ft before their engines begin to fail and fuel consumption gets critical. During this period the object gives no signals and makes no overt moves. After hovering in a fixed position for an additional twenty minutes, the object disappears going straight-up and the six F6F Hellcats return to Pasco Naval Air Station. There is no follow-up action taken after this intercept.45

Significantly, this is the very first account of any saucer-like object in Washington State. However, it should also be noted that this account is only brought to public attention in 1996 well after other significant developments in Ufology.46 There is no other documentation that corroborates this account.

August 6 and 9, 1945: The United States drops an atomic bomb on Hiroshima (August 6, 1945) and Nagasaki (August 9, 1945). The atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki has been made with the plutonium refined at the Hanford Site.47

August 12, 1945: After the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth releases a report called Atomic Energy for Military Purposes which brings the Manhattan Project to public attention.48

August 15, 1945: The surrender of Imperial Japan is announced by Japanese Emperor Hirohito, bringing the Second World War to a close. The formal surrender will be signed on September 2, 1945.

Winding Down After the Second World War

August, 1945 – December, 1946: After the end of the Second World War, the United States reduces the pace at which it is producing and stockpiling atomic weapons. At the Hanford Site, operating power is reduced in all three reactors and one of two chemical separation structures used to finalize production is shut. “B Reactor” is completely shut down in December 1946 leaving only two reactors operational.49 Though not explicitly mentioned, it is likely this coincides with a general reduction in air surveillance and protection around the site during this period.

January 1, 1947: The newly formed U.S. Atomic Energy Commission takes over research and production facilities from the Manhattan Project.50

August 25, 1947: The Manhattan Project officially dissolves.51

P.S. Did you enjoy the detailed look at these classic cases? If you want to see more of this kind of work, please:

“Remembering Peal Harbor: A Pearl Harbor Fact Sheet.” The National WWII Museum, July 11, 2008. https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/pearl-harbor-fact-sheet-1.pdf.

Hewlett, Richard G, and Oscar E Anderson. The New World, 1939/1946, A History of The United States Atomic Energy Commission, Volume I. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1962. Pg 49.

Rhodes, Richard. The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1986. Pg 307.

Marceau, Thomas, David Harvey, Darby Stapp, Sandra Cannon, Charles Conway, Dennis Deford, Brian Freer, et al. History of the Plutonium Production Facilities at the Hanford Site Historic District, 1943-1990. U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information. DOE-RL-97-1047. Richland, WA: Hanford Cultural and Historic Resources Program, U.S. Dept. of Energy, 2002. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/807939. Pg 504

Hastings, Robert. “UFOs and Nukes: The Secret Link Revealed.” UFOs and Nukes a Film by Robert Hastings, April 10, 2016. http://www.ufosandnukes.com/#trailer.

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 35.

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 504-505.

Matthias, Franklin. “Japanese Balloon Bombs ‘Fu-Go.’” Atomic Heritage Foundation, August 10, 2016. https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/japanese-balloon-bombs-fu-go#:~:text=On%20November%203%2C%201944%2C%20Japan,in%20the%20continental%20United%20States.

Mikesh, Robert. “Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America.” Smithsonian Annals of Flight 9 (1973) https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5479/si.AnnalsFlight.9. Pg 17.

Franklin, “Japanese Balloon Bombs ‘Fu-Go.’”

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 39.

Office of the Commanding General. Daily Diary United States Headquarters Fourth Air Force. Project 1947. 4 January - 25 January 1945. San Francisco, CA: Headquarters Fourth Air Force, 1945. http://www.project1947.com/fig/1945b.htm#hanford, Jan 23 Entry.

Note: While this source indicates that sightings began “this month” implying the month of January, a later account offered by R.W. Hendershot will place the beginning of aircraft sightings in December 1944. “This month” can more accurately be interpreted as circa December 23, 1944 with a second sighting occurring after in late December – early January, and a third sighting occurring sometime after a battery of searchlights are moved into the area on January 15, 1945.

This distance was calculated using Google Maps “distance measurement” tool between the Hanford Site location and the “Old Air Traffic Tower” in Pasco, Washington. Note: a number of sources have previously placed the location of this air station as “60 miles northwest” of the Hanford Site. This is incorrect. Naval Air Station Pasco was always located in Pasco and is today the site of the modern Tri-Cities Airport.

Cunningham, Ross. “Hanford Made Material For Atomic Bomb That Hit Japs.” The Seattle Times, August 8, 1945. http://www.project1947.com/fig/1945b.htm#hanford.

Hendershot, R W. Letter to Donald E. Keyhoe. “Statement on Unusual Radar Blips at Pasco Naval Air Station.” Project 1947, October 16, 2015. http://www.project1947.com/fig/hendershot.htm.

Triggs, James M. The Piper Cub Story. New York, NY: Sports Car Press, 1963. Pg 31.

Graham, and Marco Preto. “Fu-Go Balloon Bombs.” Weapons and Warfare, September 27, 2016. https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2016/09/28/fu-go-balloon-bombs/#:~:text=The%20Japanese%20were%20aware%20that,plan%20trajectories%20for%20th%20balloons.

Down, Boscombe. “F6F Performance Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment.” WWII Aircraft Performance, September 15, 1943. http://www.wwiiaircraftperformance.org/f6f/f6f.html.

Price, Byron. “Confidential Note to Editors and Broadcasters.” Project 1947, January 4, 1945. http://www.project1947.com/fig/1945a.htm#fugo.

Office of the Commanding General. Daily Diary United States Headquarters Fourth Air Force, Jan 23 Entry.

Office of the Commanding General. Daily Diary United States Headquarters Fourth Air Force, Jan 23 Entry.

Langer, S L. Vincent and Clare Whitehead's Interview - Part 1. Other. Voices of the Manhattan Project, May 17, 1986. https://www.manhattanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/vincent-and-clare-whiteheads-interview-part-1.

Langer, S L. Vincent and Clare Whitehead's Interview - Part 2. Other. Voices of the Manhattan Project, May 17, 1986. https://www.manhattanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/vincent-and-clare-whiteheads-interview-part-2.

Office of the Commanding General. Daily Diary United States Headquarters Fourth Air Force, Jan 23 Entry.

Hendershot, R W. Letter to Donald E. Keyhoe. “Statement on Unusual Radar Blips at Pasco Naval Air Station.”

Hastings, Robert. Former World War II Fighter Pilot Bud Clem’s 1945 UFO Experience at the Hanford Plutonium Production Plant. Other. The UFO Chronicles, August 8, 2009. https://www.theufochronicles.com/2009/08/former-world-war-ii-fighter-pilot-bud.html.

Warren, Frank. Navy Fighters Chase UFO Over Hanford Atomic Plant in 1945. Other. The UFO Chronicles, October 3, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ieZB_nk3HY.

Office of the Commanding General. Daily Diary United States Headquarters Fourth Air Force, Jan 25 Entry.

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 39.

Mikesh, “Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America,” Pg 71-72.

This distance was calculated using Google Maps “distance measurement” tool between the Hanford Site location and Prosser, Washington.

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 39.

Mikesh, “Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America,” Pg 72-74.

This distance was calculated using Google Maps “distance measurement” tool between the Hanford Site location and Toppenish, Washington.

Franklin, “Japanese Balloon Bombs ‘Fu-Go.’”

Groueff, Stephane. Colonel Franklin Matthias's Interview (1965) - Part 2. Other. Voices of the Manhattan Project, October 2012. https://www.manhattanprojectvoices.org/oral-histories/colonel-franklin-matthiass-interview-1965-part-2.

Mikesh, “Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America,” Pg 75-76.

This distance was calculated using Google Maps “distance measurement” tool between the Hanford Site location and Wapato, Washington as well as Moxee, Washington.

Mikesh, Robert. “Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America.” Smithsonian Annals of Flight 9 (1973), Pg 17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5479/si.AnnalsFlight.9.

Mikesh, Pg 7, 14.

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 40.

Franklin, “Japanese Balloon Bombs ‘Fu-Go.’”

Mikesh, “Japan's World War II Balloon Bomb Attacks on North America,” Pg 76-77.

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 51.

Andrus, Walt. UFO Sighting Over Nuclear Reactor. Other. The National Investigations Committee On Aerial Phenomena, July 19, 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20060719222255/http://nicap.org/hanford.htm.

Varner, Byron D. “Living on the Edge: An American War Hero's Daring Feats as a Navy Fighter Pilot, Civilian Test Pilot, and CIA Mercenary.” Amazon. B.D. Varner, January 1, 1996. https://www.amazon.com/Living-edge-American-civilian-mercenary/dp/B0006QVG4C.

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 505.

Smyth, Henry DeWolf. Atomic Energy for Military Purposes: The Official Report on the Development of the Atomic Bomb under the Auspices of the United States Government, 1940-1945. Nuclear Princeton. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University press, 1945. https://nuclearprinceton.princeton.edu/atomic-energy-military-purposes-smyth-report#:~:text=The%20official%20public%20report%20on,Section%20during%20World%20War%20II.

Thomas Marceau et al., Pg 53.

Hewlett, Richard G, and Oscar E Anderson, Pg 651.

“1946 To 1949: Exploring Thermonuclear Weapons.” Atomic Heritage Foundation, 2019. https://www.atomicheritage.org/era/1946-1949-exploring-thermonuclear-weapons.