(1938) The War of the Worlds Broadcast

"Bedlam did reign that night, but only in newsrooms across America."

In 1923, a little over 1% of American households had a radio. In what became the fastest rate of technological adoption ever, it took only 14 years for that number to reach 75%. Americans embraced the radio faster than telephones, cars, vacuum cleaners, and the refrigerator. Most of this uptake happened during the worst economic downturn in world history (the Great Depression) and nothing would rival its impact until the VCR and television.1

In many ways, the introduction of the radio was a lot like the early days of the internet. New radio stations entered into an unregulated Wild West that had to be tamed by law, industry standards, and great big cultural fights. Old newspapers, which had previously held a monopoly on reporting the news, accused this new format of “piracy” for reading its content on air.2 And this tension wasn’t helped at all by savvy politicians who saw an opportunity to skirt bad newspaper coverage and speak directly to the public.3

This golden age of radio also prompted experimentation. The so-called “Press-Radio War” produced the earliest traces of what we would now recognize as live news coverage. And as more and more stations settled into well-developed radio networks, fresh-faced executives were happy to take creative risks to compete with each other for ratings. All this led to a very unexpected broadcast on October 30, 1938, where, without knowing it, a 23-year-old from Wisconsin lit up the country’s switchboards with his reports of an alien invasion. And though his War of the Worlds broadcast was a work of fiction, its consequences would accidentally set the tone for UFO policy for the next 75 years.

The Mercury Theatre

Orson Welles began his theatre career as part of the “Federal Theatre Project” during the Great Depression. The idea was that federal money could help employ artists, writers, and directors while exposing many Americans to shows they could not otherwise afford.4 In 1936, a 20-year-old Welles made the controversial suggestion to stage Macbeth in the Haitian Court of King Henri Christophe. The all-black cast of “Voodoo Macbeth” became a smash hit and Welles was hailed as a prodigy.5

But Welles didn’t rest on his laurels, routinely investing his earnings into more stage productions to bypass administrative red tape. This is really how he came to lean on voice acting over the radio—as a means to fund his theatre work and mount his ideas faster than his contemporaries. President Roosevelt would remark that Welles was “the only operator in history who ever illegally siphoned money into a Washington project,” and, for a time, he remained one of its greatest success stories.6

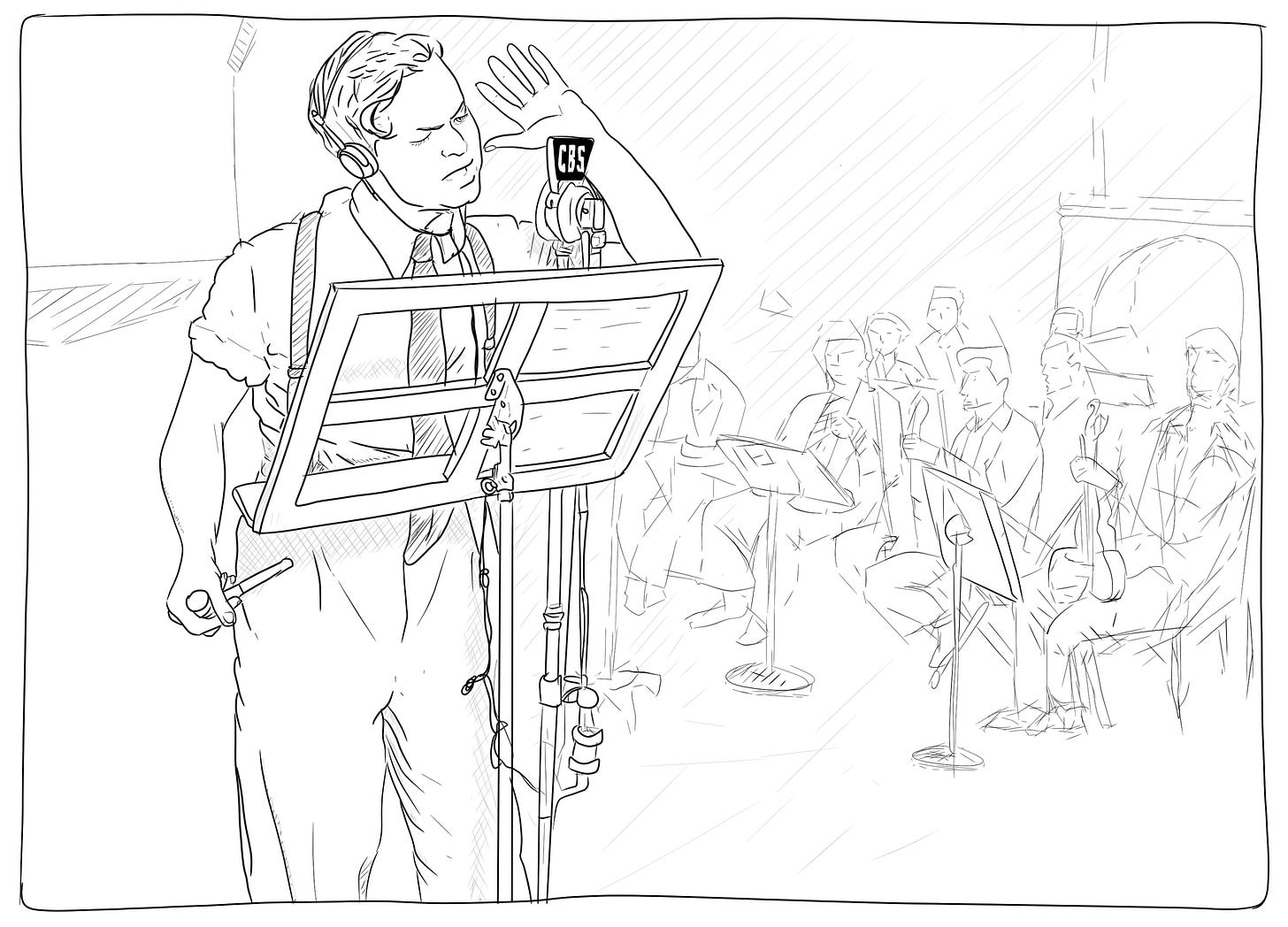

By 1937, Welles had founded his own theatre company (The Mercury Theatre) and in 1938 he received an offer to produce radio plays for CBS (The Mercury Theatre on the Air).7 The CBS format involved adapting a classic work of fiction (that could be acquired cheaply) into a one-hour radio play on Monday nights at 9:00 pm. But after an initial run of nine episodes that included stories like Dracula, Treasure Island, and The Count of Monte Cristo, CBS switched up the timeslot due to the show’s low ratings and inability to attract a permanent sponsor.8

Mercury Theatre on the Air would now come on Sunday nights at 8:00 pm and would counterprogram what was then the most popular radio show in the country (The Chase and Sandborn Hour). CBS figured that if they couldn’t get any advertising dollars, they could at least get some critical acclaim in this ultimately doomed timeslot.9 In the meantime, the plays kept on coming with Jayne Eyre, Oliver Twist, and, a week before its planned airdate, Orson Welles decided to adapt a long-forgotten 19th century novel called The War of the Worlds.10

The Invasion from Mars

Adapting War of the Worlds soon devolved into total chaos. Welles was spending most of his time on an upcoming stage production and his collaborators had trouble getting a hold of him. By mid-week, they were actively suggesting that he choose another novel and the widely held opinion over at CBS was that the show would probably “bore you to death.”11

The book had originally been written about a Martian invasion of England in the mid-1890s where, after landing and defeating several military units, the Martians reigned unchecked until they were eventually killed by disease. The story touched on major Victorian-era fears and readers were generally prompted to reflect on recent scientific discoveries and the folly of British imperialism.12

While that might have worked for a Victorian-era book, Welles’ collaborators were really struggling to find a hook for their modern American radio audience. The idea of framing the story with realistic “fake news” bulletins seemed like a promising start but, as the week wore on, each draft remained “dull” and “dated” to the men in charge of writing it.13

By the time that Welles weighed in on the day of the performance, he effectively threw out the script calling it “the worst piece of crap I’ve ever had to do.”14 This was not uncharacteristic for Welles, and, as one historian of the period would remark: “he delighted in making his cast and crew scramble by radically revising the show at the last minute.”15 But while he believed that a much stronger show would emerge from this kind of chaos, it also meant that those last minute revisions might not be very well thought out.

The Broadcast

The War of the Worlds broadcast started at 8:00 pm and largely followed the story of the novel. The first half would feature a Martian invasion (this time in New Jersey) and the second half would see a central character (Professor Pierson) navigate its aftermath. But unlike the previous plays adapted by Welles, the last-minute revisions accidentally created several, legitimate reasons for his audience to be afraid:

Normally The Mercury Theatre on the Air started with a long introduction which included a short piece by Tchaikovsky, an explanation of the radio program, and an introduction to the book being adapted. But for this particular broadcast, the introduction skipped most of this and lasted only 37 seconds.16 If you missed this intro, it would be hard to tell you were listening to a work of fiction where, by comparison, the introduction for Treasure Island lasted 4 min 20s and stated that clearly.17

Unlike other works of fiction, this one contained the names of real locations, institutions, and military units in the United States. While the names of government institutions were changed slightly (to avoid libel), none of these choices were obvious enough to betray its fictional nature.18

Although introduced in the play as the “Secretary of the Interior,” one voice actor was explicitly instructed to impersonate the sitting President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.19

Among other weapons, the invading Martians were said to be using toxic gas which was an ever-present fear since its use in World War I.20

Due to the way the script was written, the show did not have a station break at the typical half-way point (30 minutes). Audiences instead had to wait approximately 40 minutes for the broadcast to switch up the narrative and remind the audience that it was fiction.21

By the time the broadcast wrapped up at 9:00 pm, Welles was staring at two police officers who had been sent over to figure out what the hell was going on. And by the time he left the studio, Welles received the first of many questions from reporters who were already implying that the broadcast had killed “as many people as a small war.”22

Was There a Public Panic?

No. Because barely anyone heard the show. The Mercury Theatre on the Air captured about 3.6% of the American radio audience which worked out to about a million listeners on October 30, 1938.23 But what did happen was that many of those listeners placed calls to their local newspaper offices to see if what they were hearing was true. While some people were deeply frightened, most stayed close to their radios so they wouldn’t miss any important information about how to handle the emergency.24 Panicked flight did happen, but it was very, very rare. And in the very limited cases where people spooked their friends and neighbors “it was always a localized phenomenon – intense where it was felt, but not felt very widely.”25

But that’s not how the newspapers reported it. With the increasing volume of phone calls into their offices, newspapers began to put out unverified second- and third-hand accounts of panic out over the wires. It didn’t take long to build a critical mass of stories about nervous breakdowns, heart attacks, suicides, and scores of accidental deaths. By the time the morning papers hit the curb, many were reporting that “the people of the United States had succumbed to an unprecedented mass hysteria,” and, as several media critics would point out, they were thrilled to take a shot at their professional rivals on the radio.26

Even though this wasn’t true, the American public thought it was true. The newspapers effectively wrote the first draft of history and the one government organization that might have been able to clear up the myth (the fairly new Federal Communications Commission) declined to investigate. There was no government hearing, there was no government report, and the government broadly accepted the idea that the radio industry would now regulate itself.27

The closest thing to an investigation would come from a Princeton University psychologist named Hadley Cantril. In his 1940 book The Invasion From Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic, Cantril would go on to claim that 1.2 million Americans seriously panicked.28 His conclusion was deeply flawed, pre-determined before he did any research, and criticized by his own research team.29 But ultimately, that didn’t matter, and the public was now given an institutionally credible boost to the idea that “people all over the United States were praying, crying, [and] fleeing frantically to escape death.”30

UFO Policy Then and Now

This “Public Panic Myth” carried on for about 75 years. It wasn’t until 2013 that two academics really challenged the narrative and began to unwind it. 2015 saw the first accurate book about the broadcast where almost every other publication before that had accepted the panic as fact.

You could leave it there and just assume that this was a weird historical quirk, cooked up with limited information and served by people who wanted to self-promote. But that would be a mistake for those interested in American UFO policy. Because even though this War of the Worlds broadcast was fiction, almost every policy maker would have learned that the American public “freaked out” when they heard about the presence of alien life.

Obviously to our eyes it should be clear that any negative reaction would have been prompted by the reports of destruction and death as opposed to the Martians, per se. But each retelling of the public panic myth tended to downplay these details and focus on the gullibility and mass ignorance of the American public. It’s my view that this assumption almost certainly influenced the response to very real events in UFO history, and that this piece of fiction should be examined closely to see how it influenced other historical facts.

Perhaps one of the best examples of this overall negative tone comes from a 1975 NASA documentary on the potential for extra-terrestrial life called “Who’s Out There?” In this ostensibly serious video produced for school children, NASA outlines its recent accomplishments in space, a panel discussion by legitimate academics, and the experience of Orson Welles, who was happy to tell them that his little radio broadcast prompted people to “jam the highways and [take] to the hills to escape the Martians.”31 I wonder if any of those school children grew up to be policy makers.

P.S. The Other Topic is a weekly newsletter that goes out every Tuesday at 9:00 am (EST). Want free, high quality coverage of the UFO phenomenon? Join our growing community and:

Putnam, Robert. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York City, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2000. Pg 217, Table 2.

Charnley, Mitchell. News by Radio. New York City, NY: The MacMillan Company, 1948. Pg 14-19.

Craig, Douglas B. Fireside Politics: Radio and Political Culture Inside the United States 1920-1940. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2000. Pg 156.

Flanagan, Hallie. Arena: The History of the Federal Theatre. New York City, NY: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1940. Pg 17.

Hill, Anthony D, and Douglas Q Barnett. The A to Z of African American Theater. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009. Pg 179-180.

Welles, Orson, and Peter Bogdanovich. This is Orson Welles. New York City, NY: Harper Collins, 1992. Pg 13.

Schwartz, A Brad. Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News. New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2015. Pg 38, 40.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 42-43.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 43.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 45.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 58-59, 61.

Schwartz, A Brad. “The Infamous ‘War of the Worlds’ Radio Broadcast Was a Magnificent Fluke.” Smithsonian Magazine, May 6, 2015. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/infamous-war-worlds-radio-broadcast-was-magnificent-fluke-180955180/.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 49.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 62.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 63.

Koch, Howard, John Houseman, and Orson Welles. “The War Of The Worlds: The Original October 30, 1938 Broadcast.” The Mercury Theatre on the Air, October 30, 1938. https://youtu.be/crPGFZiFjfs.

Note: While Orson Welles does provide a brief monologue after the 37 second mark, there is no mention of CBS, The Mercury Theatre on the Air, or the book they are adapting. It would remain unclear to any listener if they are hearing commentary or an introduction to a fictional story.

Welles, Orson, and John Houseman. “Treasure Island: July 18, 1938, Broadcast.” The Mercury Theatre on the Air, July 18, 1938. https://youtu.be/sLXpdv0eI78.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 60.

Note: CBS executives actually reviewed the script in advance and saw no problems with it. One executive even offered suggestions to make the news bulletins seem more realistic.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 63-64, 78.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 77-78.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 80.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 96-97.

Cantril, Hadley. The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1940. Pg 82.

Note: Page 5 of this book notes that the Crossley rating service estimated a total radio audience of 32 million people for October 30, 1938. A 3.6% share of this figure is 1,152,000 people. In some cases an estimate of “4 million listeners” is provided for the War of the Worlds Broadcast which largely stems from the competing C.E. Hooper Research Organization (Page 56).

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 83-84.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 86.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 99-100.

See Chapter 7 “The Public Interest” in Broadcast Hysteria.

Cantril, “The Invasion from Mars.” Pg 58.

Schwartz, “Broadcast Hysteria.” Pg 173, 181, 183, 188, 191.

Cantril “The Invasion from Mars.” Pg 42.

Drew, Robert, and Anne Drew. “Who’s Out There?” National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), 1975. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CPkg_sJn2rU.